China’s Malacca Strait Dilemma

“It is no exaggeration to say that whoever controls the Strait of Malacca will also have a stranglehold on the energy route of China.” (China Youth Daily, 2004)

Recently, the Malacca Strait has been a focal point of concern for China and other major superpowers. This essay focuses on China’s vulnerability to the strait and possible alternatives to reduce the onus. It has been divided into five subheadings. The first part deals with the importance of the Strait of Malacca as a whole. The second part deals with China’s dependency on the strait. The third part specifies the ‘dilemma’. The fourth part specifies retorts by the Chinese scholars and security analysts in response to efforts by other major superpowers to secure the strait. The fifth part lists ways to reduce China’s dependency of the strait.

The Malacca Strait

The Malacca Strait is a waterway between Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. Connecting the Indian and Pacific Oceans, it is the shortest sea route between Europe and the Far East, and the Persian Gulf suppliers and Asian markets. It is not subject to weather extremities.

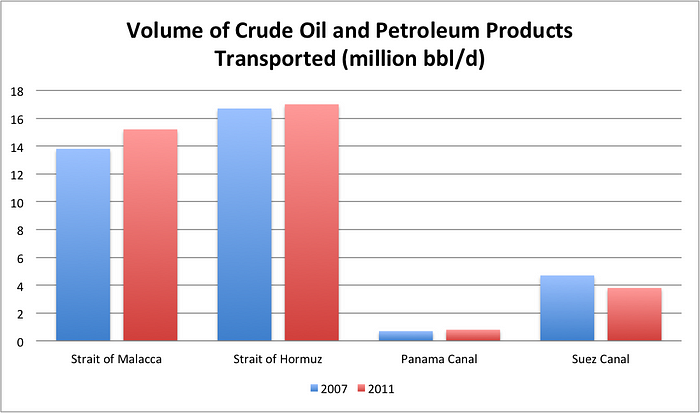

Economically, it is considered to be one of the most important shipping lanes in the world. More than a third of global trade journeys across this critical chokepoint. (Simon, 2010) It carries a major portion of world crude oil and petroleum, and almost all Chinese commodities. Nearly one-third of the 61% of total global petroleum and other liquids production that moved on maritime routes in 2015 transited the Strait of Malacca. (U.S. EIA) For comparison with other straits, look at the chart below:

Primarily, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia have sovereign control over the strait as it lies within their territorial limits. However, being so strategically important, it attracts a lot of unwanted security and piracy issues. This makes it hard for the owning states to secure it solely. China, India, Japan, the U.S. and the E.U. among others continually invest money and forces in securing the strait and developing the littoral.

China’s Dependence on the Malacca Strait

In 2015, China was the world’s largest exporter, accounting for 12% of total world export (in U.S. dollars exported). It was also the second largest importer, accounting for 10.8% of total world import. (Manorama Yearbook 2015) Of this, China depended on the Strait of Malacca for 85% of its total imports, including 80% of its energy imports. (Zhong, n.d.)

Certainly, China is vulnerable in the strait, as anybody trying to thwart this strait will also be thwarting the Chinese economy as a whole.

The Dilemma

There are major superpowers trying to influence the states controlling the strait primarily due to two reasons.

First, the strait is of crucial importance to many states’ economies, and hence it is desired that the region be unassailable and dispute-free.

Second, the advent of terrorism in the area poses a threat to society in general. According to a list issued in June 2005 by the Joint War Committee, the Malacca Strait was amongst the 21 areas worldwide in danger of “war, strike, terrorism and related perils”.

India, in 2001, opened the I.N.S. Baaz naval station to watch over the strait. It’s also developing a port in Indonesia’s Sabang as a key strategic hold in the region. Apart from this, India periodically conducts naval and anti-piracy exercise with Japan, U.S. and Indonesia in the region around the strait.

Japan has continually invested heavily in the security and welfare of the Malacca Strait. The Nippon Foundation donates millions to the Malacca Strait Council every year. Joint patrol trainings of the Japanese Coast Guard with the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) are held regularly. Japan also actively participates in anti-piracy conferences with ASEAN countries. In 2019, Japan and US had a cooperative naval deployment in the Malacca Strait.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the extensive military exercises with the Quad agonize China. And it has launched an official strategy in 2019 for a free and open Indo-Pacific. Since 2017, the Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) have provided the region with over $4.5 billion in foreign assistance.

The European Union too has heavy economic interests in the area, alongside concerns about maritime security and terrorism. They supply arms to littoral states, invest in oil exploration in the region and EU shipowners account for almost ten percent of all freight transiting the Malacca Straits. (Gilmartin, 2008) E.U. member states also have a modest military presence in the region.

While India, Japan, the U.S. and the E.U. have strong ties with the states bordering the Malacca Strait, China indeed faces a dilemma, given its tensed relations with a number of those states.

In November 2003, President Hu Jintao said, “certain major powers have attempted to dominate the Malacca Strait, which could constitute a major crisis for China.” This triggered a fear in the minds of people that, given the Indo-U.S. fraternity and the American-Sino tension owing to Taiwan, India and the U.S. could fetter China by blocking the important sea routes in the Indian Ocean. Thereon, Japan’s and the E.U.’s investments in the strait further added to their worry.

China’s response to Indian, Japanese, American and European efforts

China has not considered the aforementioned efforts warmly. Many audacious remarks were made and a lot of proposals were strongly opposed by the People’s Republic of China.

For instance, when the International Military Education and Training (I.M.E.T.), a U.S. security assistance program, was resumed in Indonesia in 2005, a leading Chinese newspaper condemned it as “targeting China and controlling its avenue of approach to the Pacific”.

Several such proposals have been termed violations of Article 34 of the Law of the Sea, which states that “The regime of passage through straits used for international navigation established in this Part shall not in other respects affect the legal status of the waters forming such straits of their sovereignty or jurisdiction over such waters and their air, space, bed and subsoil.”

The U.S., Japan and the E.U. have been continually accused of using terrorism as an excuse to increase their naval presence in and around the strait by the Chinese security analysts. Likewise, India and the U.S. have been blamed for being in collaboration to design a “China threat theory to squeeze their country’s strategic space”.

Efforts to reduce dependency on the Strait of Malacca

Looking at the dilemma, China now has three options. First, it can secure its position in the strait.

Second, it can look for alternative trading routes. Lastly, it can reduce dependence on energy import as whole, by oil conservation and promoting domestically produced coal usage.

What is China doing to secure its position in the strait?

China has greatly increased its presence in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean region. However, as Ronald O’Rourke of the Congressional Research Service said, currently, China’s naval force will not suffice in securing its critical Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs). Though world #2, it is behind the U.S. Navy in terms of equipment. Nevertheless, the navy has long term plans of constructing underground bases, building missiles and conducting naval exercises, some of which are already taking shape, like the DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missile unveiled in 2015.

To improve relations with the ASEAN states, the People’s Republic of China (P.R.C.) government has been giving them generous monetary, technical and capacity building assistance. With the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in place, China is readily exerting its influence. In September 2020, Chinese Ambassador to the ASEAN Deng Xijun said, “…..deeply realized the importance of promoting the building of a China-ASEAN community with a shared future…….”. Together, ASEAN and China have been trying to develop a Code of Conduct for the South China Sea (COC). But several obstacles remain.

To restrain other countries from intensifying presence in the Malacca Strait, China has rejected multiple security patrol propositions, and has openly condemned their involvement in the strait.

Alternative trading routes to reduce dependency on the Strait of Malacca

As part of its Belt and Road initiative, China is employing its pleasant relations with Pakistan, Myanmar and Philippines to construct and find alternative trading routes for the flow of energy supplies.

Looking at the current situation, if ships from the Gulf are to reach China without passing through the Malacca Strait, there are three options.

First, they can pass through the Lombok Strait in the Indonesian archipelago. This would incur an additional cost of 2 U.S. dollars per barrel and nearly 4 days of disrupted oil shipments. (Tunsjo, 2013) The Sunda Strait is a similar choice.

Second, they can travel around Australia to reach China. In this case, the period of disruption increases to 16 days. (Tunsjo, 2013)

Third, China can import oil from the Gulf to Gwadar port, Pakistan by sea, and thereon bring the supplies to China via the 3000 km long land ‘Silk Route’ (aka China Pakistan Economic Corridor). Gwadar is very close to the Persian Gulf and most straits will be bypassed. Currently, the rough terrain is not very hospitable. But China’s proposed 46 billion U.S. dollar investment in building the route shows that it is being worked upon. China has already acquired the right to operate the Gwadar port for 40 years from 2015. This is going to prove to be a major boon to China.

Until the silk route becomes operable, China can divide its energy supply trade between the Malacca Strait, Lombok Strait and encircling Australia and it can start building new transit routes.

The obvious alternative to the Malacca Strait will be to build another pathway linking the Indian and Pacific Oceans. One such will be a canal cut through the Isthmus of Kra in Thailand. The idea was initially proposed by the Thai government to reduce its own energy dependence on the Strait of Malacca. The P.R.C. Government agreed to sponsor the project. The project will require approximately 28 billion U.S. dollars and even though the work has started, it is not going to alleviate China’s dilemma for another decade.

To trade with Europe, China has planned an ambitious ‘Polar Silk Route’ via the Arctic. The route would greatly shorten the time, and bypass Suez and Panama canals too. Owing to thawing relations with Russia, it does not seem strategically impossible. However, given the frost, hostile climate and sparse infrastructure, its feasibility is questionable.

A second alternative is to build pipelines for the uninterrupted flow of oil and natural gas. China has three options for a pipeline:

- The first is the proposed Strategic Energy Land Bridge (S.E.L.B.), a 240km underground oil pipeline across southern Thailand. Costing only about 2.5% of the estimated cost of the Kra Isthmus Canal, it is still not very promising from China’s perspective as it will cut the cost by merely 0.5 U.S. dollars a barrel. Ships will still have to sail to and from Thailand as it will only be able to carry oil from one side to ships waiting on the other side. Also, taking into account the increasing political violence in southern Thailand, where the pipeline was proposed to be built, China did not step forward to fund this project. The Thai Government did not agree to fund it either. Thus, the idea failed to implement.

- The second is the set of oil and gas pipelines in Burma which were completed in 2015. However, given the emergence of revolts amongst separatist groups in Myanmar, this faces a considerable security threat.

- The third is the 200km Malaysia-China pipeline. Ships can be unloaded at the Eastern ports of Malaysia and thereon pipeline transport be used to reach China. While the project made some headway, the Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad canceled the project in 2018 due to fiscal problems.

In the U.S., 70% of crude oil and petroleum products travel by pipeline transport. (Conca, Forbes 2014) However, in the case of China, the rough mountainous terrain increases the construction and maintenance cost vastly. Given the revolting areas in the pathway of any proposed pipeline, it is difficult to guard the pipelines. Moreover, there is no flexibility in what can be carried, unlike in ship transport.

Embedded below is a rudimentary map of the Malacca route along with all possible alternative (and not cancelled) routes for China’s maritime trade.

Decreasing Dependence on Energy Import

According to data by the World Bank, in 2014, China’s net energy import was 15% of its total energy use. China is making an effort to decrease this number further and promote domestically produced oil. However, most of the oil fields are mature and will only decline with usage. Territorial disputes with Japan near the East China Sea have prevented China from exploiting the area’s oil content. This calls for techniques to sustain mature oil fields and a search for potential oil fields. Though China is monitoring its national oil companies very well, they really have to be made more efficient to meet China’s excessive energy demand. This can be done by implementing policies to regulate prices favorable for domestic producers.

In addition, China intends to expand the storage capacity of its Strategic Petroleum Reserve by 95 million barrels by 2020-end. (SP Global, 2020) China should continue to endorse conservation and efficient usage of crude oils.

There is also a need to emphasize the importance of natural gas and renewable energy sources and take steps to develop them. In 2019, these sources formed a small part of China’s total energy consumption: hydroelectricity 8%, natural gas 8% and renewables 5%. (U.S. EIA)

Small steps in each of these would go a long way in improving China’s economy and reducing its vulnerability to the Malacca Strait. (Remember the power of tiny gains from ‘Atomic Habits’?)

In conclusion,

China cannot bypass the Malacca Strait altogether. But it can reduce its dependency on the strait by constructing or discovering alternate pathways and dividing its shipments between those pathways. It should also try to reduce its dependency on imported energy supplies.

On a personal note, while strategic fears persist, countries must focus on working together to control the intensifying terror and piracy and keeping the strait equitably open to all.

References:

1. Mark J Valencia: The politics of anti-piracy and anti-terrorism responses in Southeast Asia

2. Simon, Sheldon W., Safety and Security in the Malacca Strait: The Limits of Collaboration. Rep. 24th ed. Maritime Security in Southeast Asia: U.S., Japanese, Regional, and Industry Strategies. The National Bureau of Asian Research

3. James Conca; Pick your poison for crude—pipeline, rail, truck or boat; Forbes; April 26, 2014

4. China set to expand commercial crude storage capacity by 15.11 mil CU M in 2020 | S&P global Platts. (2020, June 10). Essential Intelligence to Make Decisions with Conviction | S&P Global.

5. Zhong, Y., n.d. The Importance Of The Malacca Dilemma In The Belt And Road Initiative. [ebook]

6. Swanstron Niklas L.P., “The Prospects for Multicultural Conflict prevention and regional cooperation in central Asia’, March 2004

7. Oystein Tunsjo; Security and Profit in China's Energy Policy: Hedging Against Risk

8. Japan’s Initiatives in Security Cooperation in the Strait of Malacca on Maritime Security and in Southeast Asia: Piracy and Maritime Terrorism; Andrin Raj, Tokyo

9. The world’s most important trade route? (n.d.). World Economic Forum.

10. Strait of Malacca. (n.d.). Encyclopedia Britannica.

11. Resources. (n.d.).

12. Ong, E. (2020, November 9). Mainpage. FocusMalaysia.

13. Iyer, P. V. (2008, October 23). Eye on China, India and Japan ink security pact. The Indian Express.

14. Malhotra, J. (n.d.). Myanmar pipelines confirm China's place in Bay of Bengal. Business News, Finance News, India News, BSE/NSE News, Stock Markets News, Sensex NIFTY, Latest Breaking News Headlines.

15. The kra-canal project. (2015, January 14). The International Institute of Marine Surveying (IIMS).

16. Joint patrols and U.S. coast guard capacity. (2015, April 1). Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

17. Is China-Pakistan 'Silk Road' a game-changer? (2015, April 22). BBC News.

18. International. (n.d.). U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

19. Energy imports, net (% of energy use). (n.d.). World Bank Open Data | Data.

20. Dasgupta, S. (2015, April 14). China gets 40-year management rights on pak's Gwadar port, and access to Arabian Sea - Times of India. The Times of India.

21. The Christian Science Monitor. (2013, June 4). Rail vs. pipeline: How should we ship oil?

22. China’s ‘Malacca dilemma’ and the future of the PLA. (2014, November 17). China Policy Institute Blog.

23. China to bypass Malacca strait by Kra isthmus canal in Thailand. (2015, May 17). China News.

24. BS B2B Bureau. (2015, April 16). China to rely on alternative fuels to reduce dependence on foreign oil.

25.http://naval.review.cfps.dal.ca/archive/7345817-2223651/vol4num1art4.pdf

26. http://www.nippon-foundation.or.jp/en/what/spotlight/ocean_outlook/story4/

27. http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=3943#.VjL0n7crLIU

28. http://www.austrade.gov.au/International/Invest/Investor-Updates/2014/chinas-landbridge-makes-a-strategic-200m-investment-in-australian-gas

29. http://www.ukessays.com/essays/economics/the-pursual-of-global-strategic-defense-economics-essay.php

30. The Strait of Malacca, a key oil trade chokepoint, links the Indian and Pacific oceans - Today in energy - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). (n.d.). U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

31. Topic: Export trade in China. (2020, June 16). Statista.

32. Topic: Imports to China. (2020, June 9). Statista.

33. How much trade transits the South China Sea? (2019, October 10). ChinaPower Project.

34. Panda, A. (2019, May 21). US, Japan conduct cooperative naval deployment in Strait of Malacca. The Diplomat – The Diplomat is a current-affairs magazine for the Asia-Pacific, with news and analysis on politics, security, business, technology and life across the region.

35. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State - United States Department of State.

36. Gilmartin, H., 2008. EU-U.S.-China: Cooperation In The Malacca Straits. [ebook]

37. Alleviating China’s Malacca dilemma. (2017, March 13). Institute for Security and Development Policy.